Having questioned, in a previous post, some proclaimed benefits of a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, and specifically the claim that building such a reserve would strengthen the US dollar, I now wish to say something about what the proposed Bitcoin reserve will cost. In particular, I wish to discuss the cost of the BITCOIN Act’s plan to have the US government buy up to a million Bitcoins over the course of the next five years.

Too Good to Be True

“Cost?” you may be thinking; “What cost?” After all, as a recent report on the plan points out, it and some other proposals plans for establishing a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve neither require any increase in taxes nor add to the national debt. “Instead,” the report explains, “the government could leverage its existing resources, particularly gold certificates held at the Federal Reserve’s 12 banks.”

No new taxes? No more government borrowing? Glory and hallelujah! The authors of the BITCOIN Act have discovered a way to treat the taxpaying US public to a one-million Bitcoin (or, at today’s Bitcoin price, approximately $100 billion) free lunch! It seems too good to be true!

Alas and alack, and as usual, it is. Despite not calling for any new taxes or for any addition to the national debt, the BITCOIN Act is no free lunch. Instead, the proposed Bitcoin purchase will actually end up costing the government more than if the Treasury raised the necessary funds by selling securities.

To understand why, we must delve into the details of the BITCOIN Act’s “Bitcoin purchase plan.” That plan, which would have the government acquire up to 200,000 Bitcoin every year for five years, actually consists of three components. First, for five years, it would tap into the Federal Reserve System’s Treasury remittances—the interest the Fed earns on its security holdings minus Fed banks’ interest and operating expenses—devoting up to $6 billion of those remittances per year to Bitcoin purchases. Second, it would transfer $4,425 billion from the Federal Reserve System’s capital surplus account to the Treasury’s general fund, also to be spent on Bitcoin, reducing the Fed’s surplus to less than $2.4 billion. Finally, by changing gold’s official price from its present level of just over $42.22 per fine troy ounce to something like gold’s present market price of almost $2,700 per ounce, and having the Fed monetize the resulting circa $700 billion gain in the official value of the Treasury’s gold stock, it would supply the Treasury with ample funds with which to purchase up to 200,000 Bitcoins per year for five years. Were the Treasury able to buy all those Bitcoins at an average price of $100,000, those purchases would cost $100 billion, or about one-seventh of the Treasury’s golden gain. Put another way, were it to end up having to pay an average price of $700,000 per Bitcoin, the government could still afford to buy a million coins without having to draw on existing tax revenues, raise taxes, or float more debt.

Run Dry

Because the BITCOIN Act mainly relies on the third gold-revaluation method for financing a one-billion coin Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, I want to devote most of this post to assessing that part of the act’s Bitcoin purchase plan. But let’s first consider the plan’s other components.

The first of those other components—the plan to devote some of the Fed’s Treasury remittances to Bitcoin purchases—can be dealt with quickly because it’s unlikely to be taken advantage of. That’s so because, instead of earning a profit as it almost always used to, thanks to having to pay higher rates on bank reserves than it earns on the long-term securities it gobbled up during past crises, the Fed has lately been losing money hand over fist. As a result, it hasn’t sent the Treasury any money since September 2023, and it won’t do so again until it has first paid down over $200 billion in accumulated paper losses. Since the Congressional Budget Office was already predicting in June that doing so would take until 2030, the BITCOIN Act’s Fed remittance component isn’t likely to fund any substantial Bitcoin purchases.

Budgetary Slight-of-Hand

That the Fed has been running in the red doesn’t altogether prevent the Treasury from taking advantage of it to fund a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve. In fact, all three components of the BITCOIN Act’s Bitcoin purchase plan have the Fed helping out in some fashion, if only unwillingly, while the remittance-diversion plan alone depends on its turning a profit.

Instead of relying on those profits, the Bitcoin purchase plan’s second component has the Treasury grabbing most of the Fed’s capital surplus. Even now, at $6.8 billion, that surplus is paper thin compared to its $29.3 billion level when the FAST (Fixing America’s Surface Transportation) Act was passed in December 2015. Having failed to agree to legislation that might have allowed the FAST Act’s $305 billion price tag to be fully paid by traditional means, Congress chose instead to limit the Fed’s surplus capital to $10 billion. Doing so forced the Fed to immediately fork $19.3 billion over to the Treasury, which added it to the Highway Trust Fund. Two 2018 appropriation bills transferred another $3.2 billion of the Fed’s surplus capital, capping it at its remaining, lowered level of just $6.8 billion.

Although the FAST Act wasn’t the first time Congress treated the Fed’s surplus as a source of off-budget funding—in 1933, it drew on it to provide the FDIC’s working capital—the 2015 measure marked the first use of the Fed’s capital to fund activities having nothing to do with monetary or bank regulatory policy. So it’s pretty obvious that the BITCOIN Act’s plan to once again raid the Fed’s capital was inspired by the FAST Act precedent.

What’s wrong with that? The same thing that was wrong with the FAST Act’s own Fed raid, namely, that even if it did the Fed no harm, it amounted to what former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke called “a form of budgetary sleight-of-hand that would count funds that are already designated for the Treasury as ‘new’ revenue.” As Bernanke explained when the FAST Act was in the works, to actually come up with the $19.3 billion it owed the Treasury, the Fed had to sell securities, thereby reducing its future earnings and future Treasury remittances. “The net effect,” Bernanke says, “is precisely the same as that resulting from the issuance of fresh government debt.” Cato’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives adjunct scholar Jeff Hummel reached the same conclusion while supplying further details. So did a 2002 GAO study of the general fiscal consequences of reducing the Fed’s surplus capital. “Amounts transferred to the Treasury from reducing the [Fed’s] capital surplus account,” the study says, “would be treated as a receipt under federal budget accounting but do not produce new resources for the federal government as a whole.”

Nor is it certain that reducing the Fed’s surplus capital to avoid raising taxes or increasing the national debt does no harm. Although it’s true that fiat-money issuing central banks can operate without capital, as a 2017 GAO investigation reports, academics and Fed officials worry that the practice “might lead the public and financial markets to question if the Federal Reserve was independent from the executive and legislative branches.” The GAO also concluded that such questioning becomes more likely when recurring transfers threaten to eventually reduce the Fed’s capital to zero.

Striking Gold

So we come to the third and most important component of the BITCOIN Act’s Bitcoin purchase plan: the funding of Bitcoin purchases using the proceeds from gold revaluation and monetization. Although the Federal Reserve banks haven’t owned any gold since January 1934, their assets include Treasury gold certificates worth over $11 billion. Those certificates are backed by an equal sum of gold, according to its official price of just over $42.22 per troy ounce. The gold itself is owned by the Treasury and stored at Fort Knox and various other Treasury depositories. Were the BITCOIN Act to pass, gold’s official price would be raised to its market price. Assuming a market price of $2,700 per ounce, that would make the Treasury’s gold officially worth almost 64 times its present value. The Treasury would then swap new gold certificates reflecting gold’s higher official price for the ones now in Fed banks’ possession. Upon receiving the new certificates, the Fed banks would have 90 days in which to “remit the difference in cash value between the old and new gold certificates to the Secretary for deposit in the general fund,” thereby monetizing the Treasury’s accounting profit.

Still assuming gold to be worth $2,700 per ounce, these transactions would yield the Treasury a tidy sum just shy of $700 billion. Were the Treasury able to buy a billion Bitcoin at an average price of $100,000, or somewhat more than Bitcoin’s actual market price as I write this, the gold monetization scheme would give the Treasury seven times the sum needed for the purchase, without the government having to raise more tax revenue and without adding a nickel to the national debt!

Backdoor Borrowing

As I noted before, this sounds too good to be true. The catch is that, although it’s strictly true that the plan calls for no increases in taxes or the national debt, it’s no bargain; because despite not raising the national debt, it turns out to be equivalent to having the Treasury borrow $100 billion (or whatever its Bitcoin purchases end up costing) directly from the Fed (putting-up gold as collateral), and indirectly from the nations’ banks, at interest rates that are higher, and perhaps much higher, than it could get by selling securities.

To see why, let’s consider how the various operations just described affect both the Fed’s and the Treasury’s balance. Once again I’m assuming that revaluing the Treasury’s gold stock raises the value of its gold by $700 billion. To monetize that gain, the Treasury takes back the Fed’s existing gold certificates and gives the Fed new ones worth that much more. The Fed then credits the Treasury General Account (TGA) by the same amount. So we have, in billions:

Federal Reserve:

Assets (Gold Certificates) + $700; Liabilities (TGA Balance) +$700

Treasury:

Assets (TGA Balance) + $700; Liabilities (Gold Certificates) +$700

So far, so good. But the Treasury still has to buy a million Bitcoins. Let’s assume, as before, that doing so costs $100 billion. Let’s also assume, heroically, that the Treasury resists spending any more of its apparent $700 billion windfall. The new dollars spent on Bitcoin get deposited with US banks, increasing their reserves. The changes are:

Federal Reserve:

Liabilities (TGA Balance) -$100; Liabilities (Bank Reserves) +$100

Treasury:

Assets (TGA Balance) -$100; Assets (Bitcoin) +$100

Once again, what the government has done is finance a $100 billion Bitcoin purchase with what amounts to a permanent $100 billion interest-free Federal Reserve loan, collateralized by that much of the Treasury’s increased nominal gold hoard. Although the Fed doesn’t directly charge the Treasury any interest on the $100 billion credited to the TGA, the Fed itself finances that credit by borrowing $100 billion more from the nations’ banks. And those banks do charge interest, as it were, at whatever rate the Fed pays on bank reserves. Since gold certificates earn no interest, the whole operation reduces the Fed’s profits and Treasury remittances by the full amount of those additional interest payments. The overall fiscal burden is therefore much as it might be were the Treasury to borrow $100 billion directly from the banks at the same rate the Fed pays them. But since the lending is financed by bank reserves instead of new Treasury securities.… Hey presto! It isn’t counted as part of the national debt.

Yet national debt it is, economically if not officially. And costly national debt at that. How so? At 4.65 percent, the current interest rate on bank reserves is higher than six-month and one-year Treasury bill rates of 4.26 percent and 4.27 percent, respectively. And it is much higher than the rate on three-year Treasury notes, which is now just 4.08 percent. Nor is the present situation unusual: The interest rate on reserves, being an overnight rate, is generally higher than rates on longer-term Treasury securities. Assuming that the Treasury holds all the Bitcoins it purchases for 20 years instead of selling any to pay off the national debt (the only options the BITCOIN Act allows), during that time banks will have earned, and the Fed will have lost, more than $150 billion as a result of the government’s Bitcoin investment. Were the Treasury instead to raise the money needed to buy a million Bitcoins by selling $100 billion worth of three-year Treasury notes, the interest cost would be about $125 million, or $25 billion less.

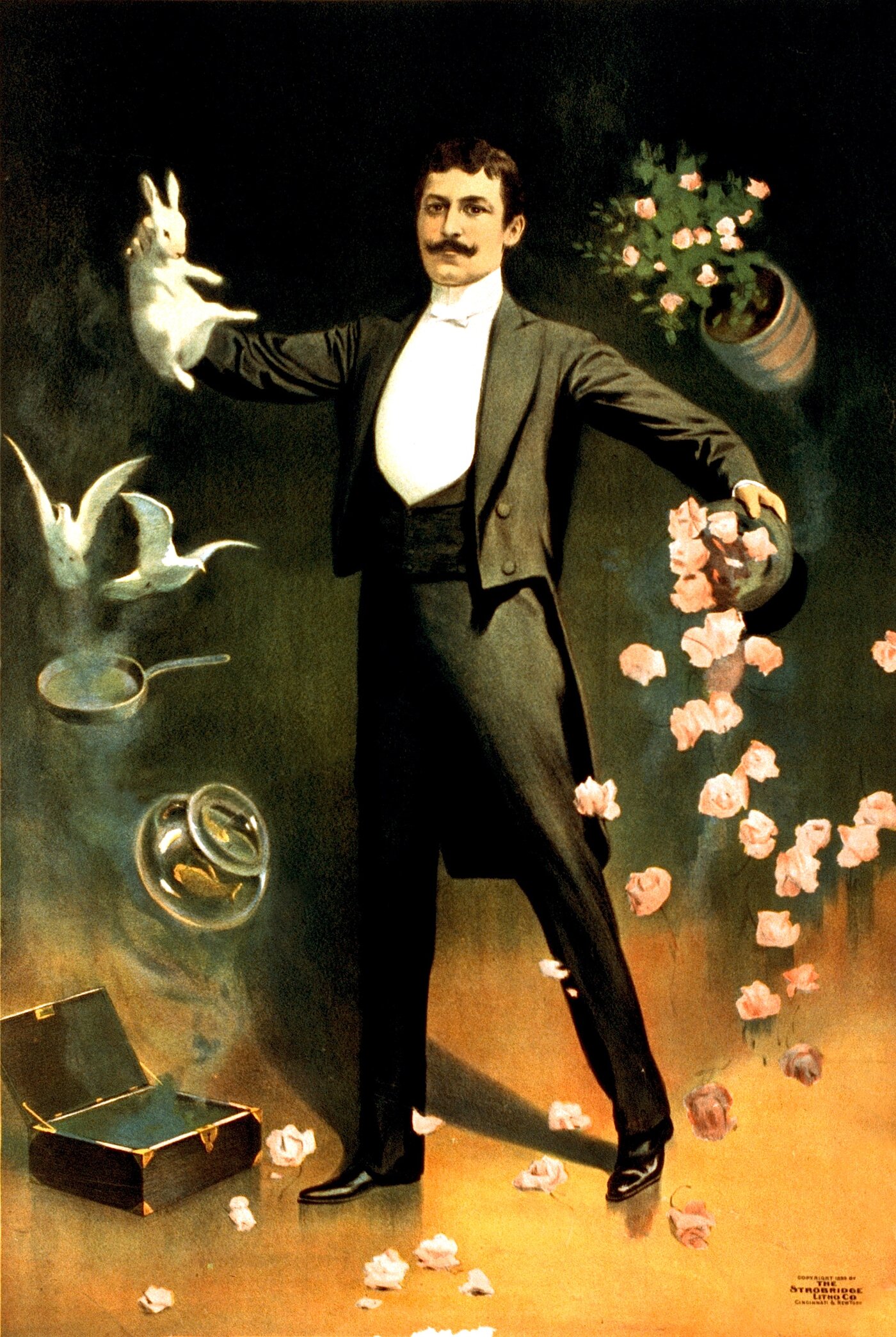

It’s $25 billion less, but more visible, for were the Treasury to finance its Bitcoin purchase by issuing more securities, the national debt would go up; and it is precisely in order to avoid having the debt go up, to skip past the ordinary appropriations process, and to otherwise pull the wool over Americans’ eyes, that the BITCOIN Act relies on so much gold-plated hocus pocus. What better way, after all, to gain the public’s support for a plan that may only serve to pump Bitcoin holders’ bags than by making it look like it won’t cost a thing?